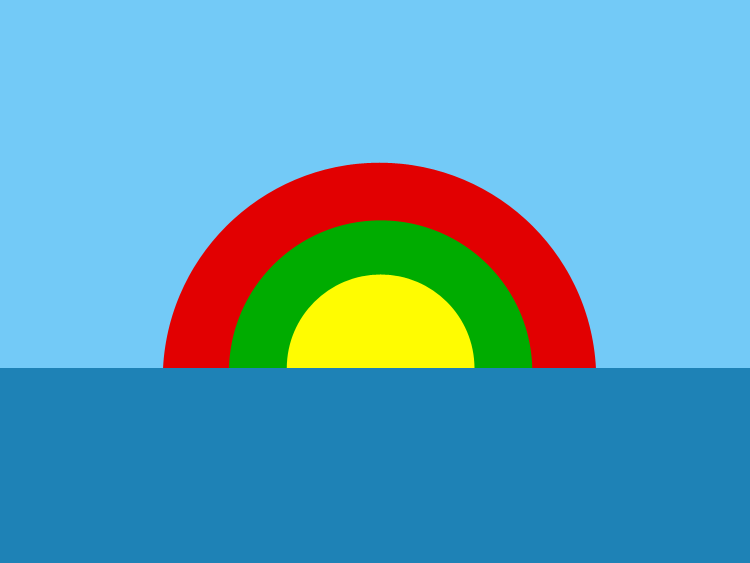

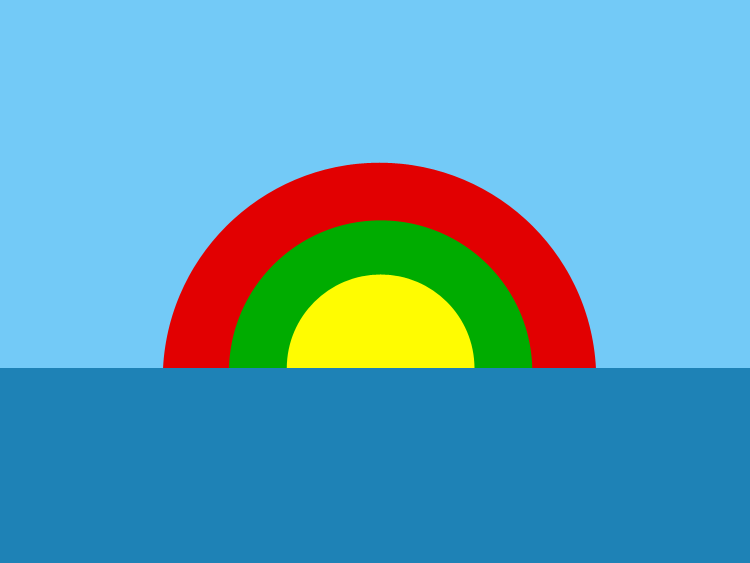

The logo drawn and colored from my sketch is meant to symbolize the rise of plant and animal life and the dawn of humanity on Earth.

The lower third of a six by eight unit rectangle is colored ocean-blue. The upper two-thirds is colored sky-blue. In the middle, centered on the boundary between the blues, a golden-yellow circle of one unit radius is surrounded by a chlorophyll-green annular area which is surrounded by a blood-red annular area, all half hidden by the ocean-blue. Their radii are 1.000, 1.618, and 2.310, respectively.

The touch of sophisticated human mentality can be inferred from the logo’s dimensionality. Several thousand years ago a student of Pythagoras would notice that the length of the diagonal of the rectangle is ten, the mark of man, counting on his fingers.

Pointing to modern science, the area ratio of the red annulus to the yellow circle is Napier’s number, e = 2.719. It appears ubiquitously in mathematical descriptions of action in the phenomenal world.

The area ratio of the green annulus to the yellow circle is equal to Phi, the golden mean (φ = 1.618). It often appears in the proportions of rectangular figures of art and architecture. The circumference of the circle of unit radius is two-pi (2π), the radian measure of one rotation or cycle of repetitive action. Vorticity characterizes the universe from the submicroscopic to the galactic.

The golden color of the circle suggests the light of intelligence and the radiance of love and peace of the creator and enjoyer of this mysterious game of existence.

The logo looks like a sunset. It is ambiguous. At a glance, you might hear a voice that shouts:

“Stop! Eastwards from the Golden Gate and across the bay, at Oakland Technical High School, Professor Silas Coleman stands before the senior class he teaches from the carefully crafted textbook he wrote on classical physics.

It is 1930, Spring. A fit figure, he stands five feet four inches tall. Well groomed, graying hair, a pair of pince-nez glasses hangs on his vest above the watch chain. He glances at the clock, then takes the roll by a glance at the class. (All twenty-four selected, orderly and courteous young men are sitting quietly in their assigned seats.)

He greets the class, strokes his little Van Dyke beard, and places a block of wood on the table. A student laughs, others do, too. That block was set before their eyes time after time at their first meetings last Fall.

Be quiet and listen.

You’re drunk

and we are at the edge of the roof.”

- from the Persian poet Rumi